DIMPLE's Energy Landscape

This blogpost is about the theoretical adventure I've had in exploring the inner workings of the DIMPLE FPGA Ising machine system and finding out just how good of a little machine it really is.

Oscillator-Based Ising Machines

An Ising Machine, is a machine that assigns each binary string \(\mathbf{s}\) of length \(n\) with entries \(\pm 1\) (\(\mathbf{s}\in \{+1,-1\}^n\)) an energy given by:\[E(\mathbf{s})=-\sum_{i,j} J_{ij} s_i s_j - \sum_i h_i s_i=-\mathbf{s}^T \mathbf{Js}-\mathbf{h}^T\mathbf{s}\]Where \(\mathbf{J}\) is called the coupling matrix and \(\mathbf{h}\) is called the bias. This energy in turn describes the statistics of the Ising machine, where the probability that the machine is found in any given state is given by:\[\mathbb{P}(\mathbf{s})=\dfrac1Z\exp\left(-\beta E(\mathbf{s})\right)\text{ with } Z=\sum_\mathbf{s}\exp(-\beta E(\mathbf{s}))\]We call \(\beta\), the "inverse pseudotemperature", the origin of the Ising machine is the physical Ising model but aside from the mathematical similarities and possible physical instantiations of Ising machines this is where all similarities end.

Ising machines have been researched for a few decades now and have realizations in D-Wave's Quantum Annealers, Coherent Ising Machines, Simulated Ising Machines and the most relevant for us "Oscillator-Based Ising Machines".

Oscillator-Based Ising Machines are arrays of coupled oscillators where the general story is a tunable mutual loading, that is, as the oscillators fall in and out of sync with one another some physical effect will cause the oscillators to lag or lead on their natural frequency, gradually pushing the oscillators in and out of sync. The generic model that's used to describe this phenomenon is the Kuramoto oscillator system, where the dynamics of individual oscillator phase \(\phi_i\) with natural frequency \(\omega_i\) are given by:\[\dfrac{d\phi_i}{dt}=\omega_i-\sum_j K_{ij}\sin(\phi_i-\phi_j)\]The Kuramoto system is a conservative system, so we can rewrite the dynamics in terms of the gradient of a scalar field that we can call "the energy":\[\dfrac{d\phi}{dt}=-\nabla \cdot \left(\sum_{i,j} K_{ij}\cos(\phi_i-\phi_j)+\sum_i \omega_i \phi_i\right)\]If we assume that the \(\phi_i\)'s fall into either phase or antiphase with some reference oscillator (as is typically the case for "phase-locked" systems - the above energy starts to look an awful lot like the energy given to define the Ising Machine to begin with.

Since this is a conversative gradient system, we notice that energy and wave form are pretty clearly related and so, any non-linearity that shows up in the waveform is reflected in the energy and vice-versa by a simple derivative relationship.

DIMP-wut?

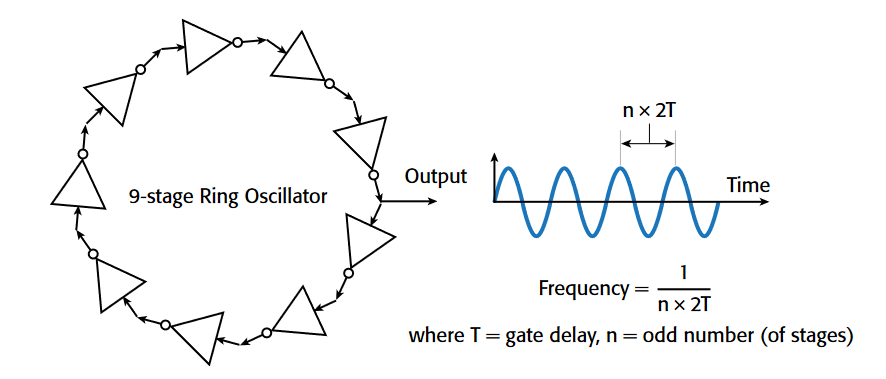

Digital Ising Machines with Programmable Logic, Easily! (DIMPLE) is an FPGA design by Zach Belateche to realise a "Oscillator-Based Ising Machine" using digital logic. The underlying principle is that we rethink oscillator based Ising machines as long chains of buffers with a single inverter:

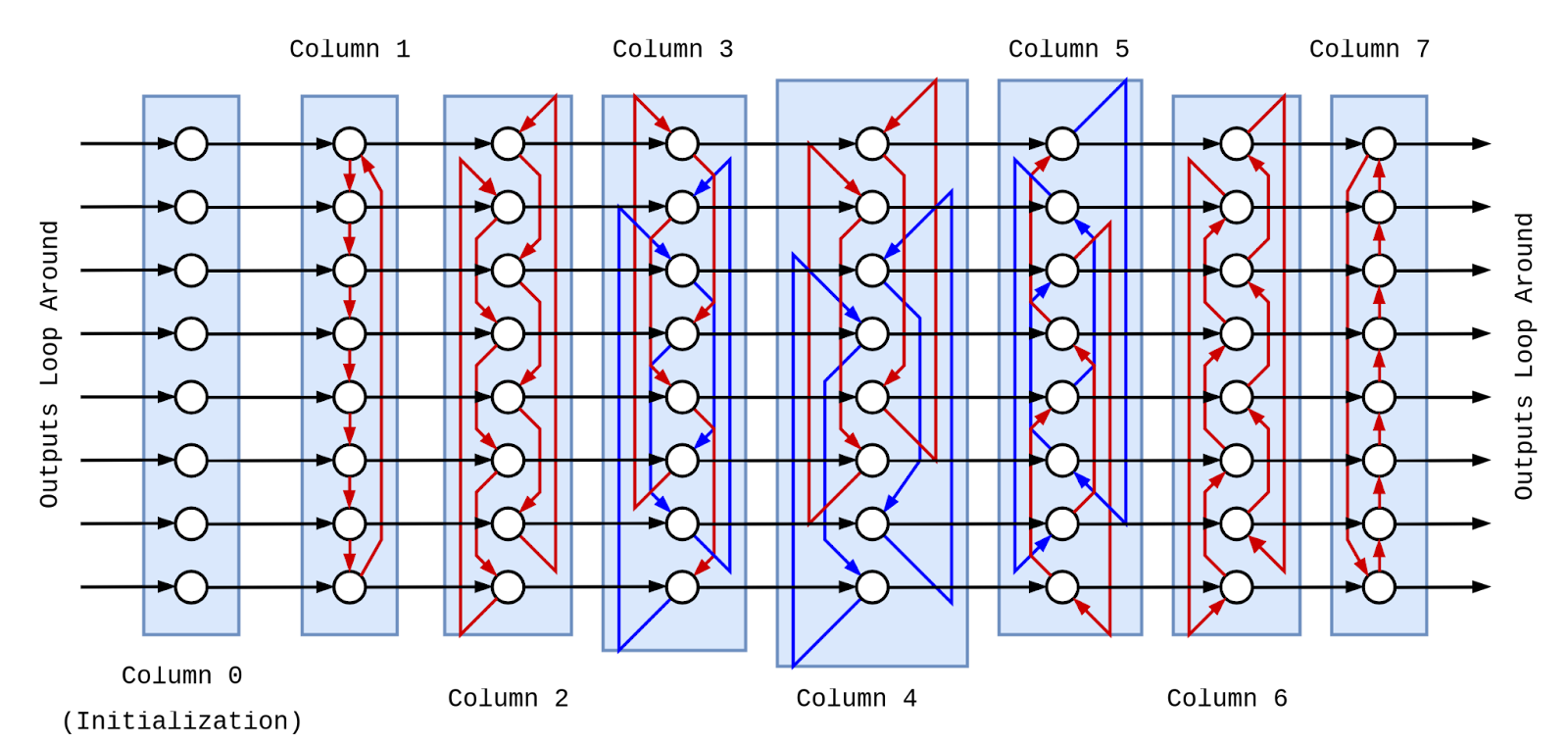

These run asynchronously and different stages are being XOR'd with each other in a complicated rotating coupling pattern showed below:

In a given coupling cell, if this XOR is 1 and there is an approaching wavefront in the coupling cell - this wavefront will be rerouted onto a longer or shorter track than the default leading to the phase of the wave effectively changing by some constant amount defined in the coupling cell's weight (a nice consequence of this is that unlike in analog OBIMs, \(K_{ij}\neq K_{ji}\)):

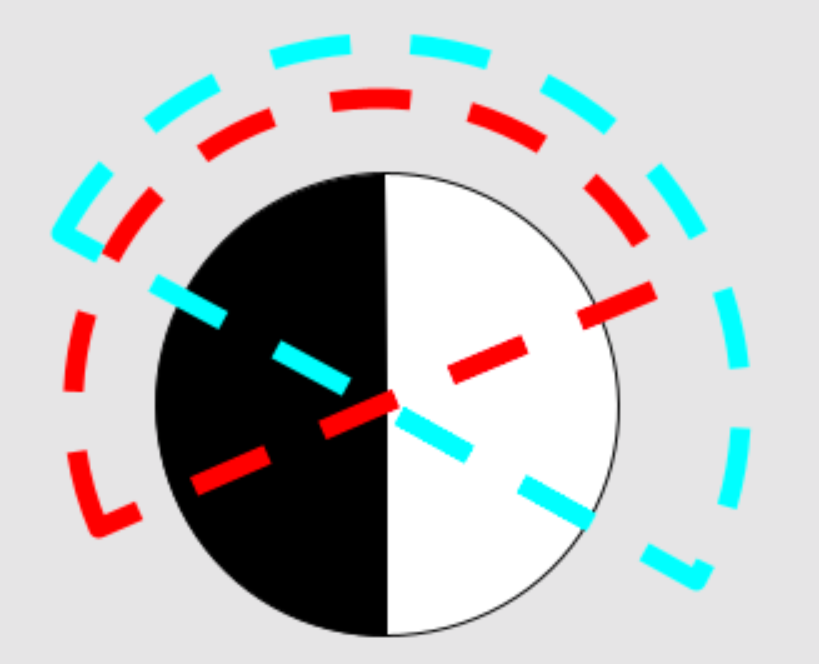

A good mental model to think about how this relationship actually works is by rethinking what the values of the buffer chain look like during operation, effectively spreading the buffer chain over the length of semicircles and imagining a virtual inverter at its corners that cover a spinning half moon representing the full range of states possible on a buffer chain with a single inverter:

We can imagine that the coupling stage of the oscillator for a given pairing is located somewhere on the semicircle that the coupling cell is on, giving us the relationship between phase and the coupling cell at any given oscillation, we have that \[\text{XOR}(A,B)=\text{H}(\sin(\phi_A-\phi_B))\]Where \(H\) is the Hadamard transform, \(H(x<0)=0\) and \(H(x\geq 0)=1\).

Then we can say that with each XOR per oscillation, the phase is shifted by the quantity stored in the weight, since we have a constant shift with a constant time we can use the calculus heuristic to get the dynamics: \[\dfrac{d\phi_i}{dt}=\omega_i - \sum_j K_{ij} H(\sin(\phi_i-\phi_j))\] To repeat the energy derivation again, we can take the integral of this system since it is conservative yield the following the following scalar field:\[\dfrac{d\phi}{dt}=-\nabla\cdot\left(\omega_i\phi_i - \sum_{i,j} K_{ij} \max\{0,\phi_i-\phi_j\}_{[-\pi,+\pi]}\right)\]For those who've been around neural networks, you'll recognize this as a periodic ReLU relationship.

But is it Ising?

One of the fundamental questions that I had when I became the DIMPLE system's biggest fan, is that I wasn't sure how or even if it would converge. Zach had run some experiments which betray the kinds of distributions we would expect from a complicated machine with fine-detail balance, ie. a Boltzmann distribution... but how good was DIMPLE at maximizing Ising Hamiltonians?

Fortunately, independently of us, Mikhail Erementchouk and gang were busy learning about the pitfalls of Oscillator-Based Ising Machine design and proposing a model of computation that almost exactly corresponds to DIMPLE!

QKM\(\leftrightarrow\)XY\(\leftrightarrow\)BZM

The first paper of Mikhail's that caught my eye was "On Computational Capabilities of Ising Machines based on Non-Linear Oscillators" - in it Mikhail makes the follow observation, the Kuramoto model where we assume that all oscillators have the same period, is the same thing as the classic XY model of ferromagnetic materials which in turn is a rank-2 semidefinite programming problem sometimes called the Burer-Zhang-Monteiro Heuristic.

In the paper, Mikhail proves two important results, the first is that since Kuramoto systems are identical to BZM, we know that Kuramoto systems converge to 0.87 of optimal value in arbitrary graphs in polynomial time (which is optimal if the Unique Games Conjecture is true) with higher convergence emerging in a presumed superpolynomial regime but it is an unsolved problem. The second is that Kuramoto rounding problem is non-trivial requiring a heavy duty processing step to choose the correct phase direction as "spin up" in order to get this 0.87 guarantee - and even this delicate anisotrophic state can be destroyed by contemporary methods used to stabilize Kuramoto systems like Sub-Harmonic Injection Locking.

The \(V_2\) Model

To resolve these issues, Mikhail proposed an alternative model in "Self-contained relaxation-based dynamical Ising machines" to the Kuramoto system which he dubbed \(V_2\), \(V_2\) dynamics are given by:\[\dfrac{d\phi_i}{dt}=\omega_i-\sum_j K_{ij}\ \text{sgn}(\sin(\phi_i-\phi_j))\]Where \(\text{sgn}(x<0)=-1\) and \(\text{sgn}(x\geq 0)=+1\), so we repeat the derivation to get an energy scalar field:\[\dfrac{d\phi}{dt}=-\nabla\cdot\left(\omega_i\phi_i - \sum_{i,j} K_{ij} | \phi_i - \phi_j|_{[-\pi,+\pi]}\right)\]Where \(|\cdot|_{[-\pi,+\pi]}\) is taken to be absolute value function that is periodic in \(2\pi\) intervals.

Mikhail goes on to prove a few nice properties of this machine, firstly, that it respects the same polynomial convergence guarantees that he achieved in his first paper, then that the \(V_2\) model solves the Kuramoto rounding problem, no matter which direction you choose, it will always be the optimal rounding or better and finally, Mikhail shows that with stochastic perturbations a \(V_2\) model will converge to the optimal solution of a problem almost surely in superpolynomial time (the jury is out as to if this is exponential or doubly exponential in time).

Is DIMPLE a \(V_2\) model?

The answer to this question is in fact, yes.

To see why, we show the following equivalence between the two models dynamics: \[\dfrac{d\phi_i}{dt}=\omega_i-\sum_j K_{ij} H(\sin(\phi_i-\phi_j))\qquad\text{D.I.M.P.L.E}\]\[=\omega_i-\sum_jK_{ij} \left(H(\sin(\phi_i-\phi_j)-\dfrac12+\dfrac12\right)\]\[=\omega_i-\dfrac12\sum_jK_{ij}-\dfrac12\sum_j K_{ij}\ \text{sgn}\left(\sin(\phi_i-\phi_j)\right)\quad V_2\text{ model}\]So DIMPLE with some clever manipulation of its phase drift recovers the dynamics of an arbitrary \(V_2\) machine and all of its advantages.

Where to next?

Now that we have a picture beginning to emerge of just what DIMPLE is, we have some critical questions remaining - how fast is the superpolynomial convergence of the system, does this mechanism lend itself to a level of understanding that would allow us to construct more efficient digital Ising machines? These are the questions that I intend to cover and more as we explore this new avenue of parallel annealing hardware.